We at the British Omani Society are happy to host this wonderful piece of writing from Dr. Ibtisam Al- Wahaibi, Head of Business Communication unit at College of Economics and Political Science at Sultan Qaboos University. She has published a number of research papers in academic journals about socio-cultural anthropology of Omani Bedouins focusing on camels and human relations.

Below are excerpts from Dr. Ibtisam's upcoming book entitled God’s Gift to Bedouin: Camel Traditions of the Wahiba People of Oman, which will be published later this year.

Generally, humans tend to perceive animals as a commodity or resource, and to value them,or not, according to how useful or productive they are. This is especially true in the Arabian Gulf. Generally speaking, Arabs only give attention and care to those animals that fulfil utilitarian purposes. Camels, however, fall into a category of domestic animals that are treated with respect and even a sense of worship due to their significant contribution to the prosperity of a household, the honour of a tribe, and also due to their perceived sacred nature. The camel’s qualities are praised in the Qur’an: ‘Do they not look at the camels, how they are created’ (Qur’an 88: 17), while the Bedouin describe the camel as ‘Ata Allah’ or God’s gift. This name relates to an account in the Qur’an (Qur’an 7:73-79).

The views and disposition of the camel owners themselves have been strongly influenced by their involvement with the camel. Aesthetic preferences, social status and identity, sense of compassion, and psychological stability and health are among those aspects where humans have been affected by their interactions with camels.

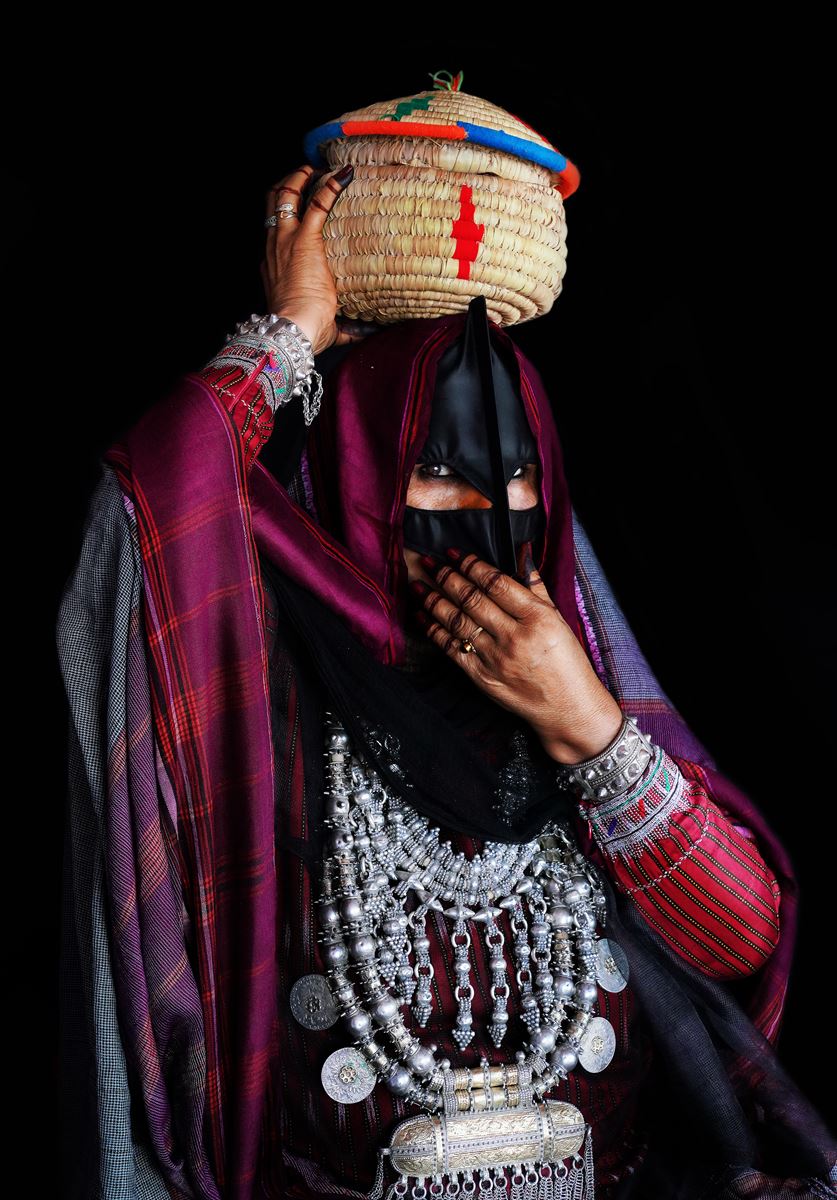

Aesthetically, camel owners use camel beauty standards to establish a concept of beauty in the woman. These standards include a long neck, thick eye lashes, and a particular body shape with features similar to racing camels: slim, with a clearly defined waist and a wide chest. In other words the figure should be curvaceous but not fat. The Bedouin dialect of Arabic boasts an abundance of metaphors used to describe a beautiful woman by comparing her with a camel. For example, the retired camels which take part in the Ardha contest are described as talee`a, while beautiful women are also called Talee`a. The main characteristics of Talee`a are to walk in pride and confidence and to have physical characteristics such as a narrow waist, long neck and expressive eye gaze. Such a camel walks with her head up, knowing that she is beautiful; the same applies to a woman’s beauty. It’s all about the way she sits and her posture.

Aesthetically, camel owners use camel beauty standards to establish a concept of beauty in the woman. These standards include a long neck, thick eye lashes, and a particular body shape with features similar to racing camels: slim, with a clearly defined waist and a wide chest. In other words the figure should be curvaceous but not fat. The Bedouin dialect of Arabic boasts an abundance of metaphors used to describe a beautiful woman by comparing her with a camel. For example, the retired camels which take part in the Ardha contest are described as talee`a, while beautiful women are also called Talee`a. The main characteristics of Talee`a are to walk in pride and confidence and to have physical characteristics such as a narrow waist, long neck and expressive eye gaze. Such a camel walks with her head up, knowing that she is beautiful; the same applies to a woman’s beauty. It’s all about the way she sits and her posture.

Many of the Bedouin poems that describe women’s beauty link it to the camel’s physical characteristics, especially the eye gaze, the narrow waist line, and the elegant back. Camel terminology is also used to describe old ladies negatively, for example an old camel is called fater, فاطر meaning no longer fertile and not used for racing or Ardha. Therefore, if an elderly woman is trying to look and act younger she will be called fater, it is a way of putting women down who ignore their age and try to look younger in one way or another.

The quality of a camel has a significant effect on its owner’s social status. Ownership of a high-breed camel creates a feeling of equality with sheikhs and people of high social standing. As one of the interviewed camel owners said, ‘I am a regular man with an average income. But on the race track I am equal with His Majesty if the camel owned by him competes with mine. It gives me a feeling of pride and confidence.’ It doesn’t matter if the owner is rich or poor, a sheikh or a common person, on the race track and in the camel community they are all equal and they will be treating each other as part of the group, so owning a camel gives a sense of inclusion.

Lay people not initiated into the camel rearing business perceive camel owners as bounty hunters who raise the animals for profit. But the camel owners identify themselves as extraordinary human beings. They feel that they are part of a culture that is superior to any other culture, due mostly to the camels being perceived as sacred. Therefore, as a sign of love and special bond with camels, owners are often known in the community, and prefer to be called by, the name of their favorite camel, e.g. ‘the owner of Samha’. Moreover, this name can be inherited from an ancestor, the first owner of a particular camel. One of the camel owners that I interviewed shared the following: "I am called by the name of my grandfather’s camel, Aladhba. I am proud to have the privilege to carry this name. Although I have many camels and some of them are very competitive and winning camels, I will always be the owner of Aladhba and my kids will carry the same name in the future."

Moreover, reading the body language of camels and responding to their needs teaches owners to move beyond self-interest, fostering compassion and empathy. In 50% of narratives camels are described as partners. They give their owners love, empathy, support that is similar to the emotion they receive from their family members. Specifically, children described their favorite camel as " Best friend" or a "sister". One owner highlighted camels' unique patience and adaptability, appreciating their gratitude for both abundance and scarcity. This mutual care and understanding reflect the unconditional love shared between camel and owner, deepening the bond and emphasizing the emotional richness in these relationships.

Camels and Emotions

Primary emotions, such as fear and fight-or-flight responses, are innate, automatic reactions requiring no conscious thought. These include Darwin's six universal emotions: fear, anger, disgust, surprise, sadness, and happiness. Animals, including camels, exhibit such emotions almost instinctively. Secondary emotions, on the other hand, involve higher brain functions and conscious thought, encompassing complex feelings like regret, jealousy, and longing. These emotions shape responses to primary emotional triggers, influencing behaviors based on situational context and past experiences.

Interviews with camel owners suggest that camels experience emotions akin to humans. For instance, camels exhibit pride, shame, and even a sense of ego, particularly evident in competitive settings like races. A winning camel might display pride, while a losing one might express shame through body language. Owners report that camels can anticipate races, demonstrating excitement or dread based on their preparation.

One owner recounted a proud, self-reliant camel who controlled her training pace. Despite her potential, she faltered in a race when overtaken, giving up entirely and finishing last. Afterward, her behavior suggested guilt and disappointment, as she avoided food and interaction.

Camels show guilt through their gaze and demeanor. An owner described a camel, Ishaqah, who bit him playfully but hurt him unintentionally. Upon realizing her mistake, her regretful expression mirrored that of a child seeking forgiveness.

Camels also mourn the loss of their owners or companions. One camel cried and refused to leave a funeral until comforted by the father of the deceased camel owner. Another group of camels grieved for three days after their owner bid them farewell before his death, demonstrating deep emotional bonds with humans.

One owner described his camel that express joy when she unite with him after being a part for almost a year similar to children when they greet their parent after a long absence. However, they can display resentment if mistreated. An owner shared how his camel, Khamisah, led a herd away after being neglected. Despite the fact her owner punished her, Khamisah repeated her protest, showcasing her intelligence and strong-willed nature.

Some camels recognize their names, owners' voices, or even subtle gestures, responding accordingly. For example, a camel might interpret a finger point to stop drinking water or signal her pregnancy by raising her tail and head.

In every culture or society there are some values that are more important and can be considered a priority in comparison to other values. For Bedouin society, key values are generosity, and offering help and support to others, even on occasion to others that you don’t know or that you don’t have a direct relationship with. Generosity, and the ability to offer help without questioning, is a trait the camel owners should have. Old camel men describe a man who is mean, not supportive, stingy, with the traditional saying ‘he never rode a camel’.

They attribute a person’s good deeds to his relationship with the camel. If the man is attached to a camel or raises a camel, he will be a man with good attributes such as generosity and supporting others, but if the person does not have these traits this can be explained by his not having a camel, because for them having a camel is the key to acting like a real man.In conclusion, the owners’ relationship with their camels is very special and deep-rooted, it’s a combination of sincere love, pride, and even addiction to them; they spend from5 to 7 hours daily in their camels’ enclosure.

About the author:

About the author:

Dr. Ibtisam Al- Wahaibi, Head of Business Communication unit at College of Economics and Political Science at Sultan Qaboos University. She completed her Phd at the University of Sheffield in Communication and Management field. She did two masters degrees from the University of Bond ( Australia) in Corporate communication and Master of Management research from the university of Sheffield. This book was drafted during her research year at the university of Sussex ( United kingdom) in 2021. She published a number of research papers in academic journals about socio-cultural anthropology of Omani Bedouins focusing on camels and human relations. She presented her work on Bedouin societies anthropology on many international conferences in Europe and Asia.

She is certified trainer from the university of Arizona and work as a trainer at the Royal academy of Management. She is from the Wahibi family in east part of Oman.