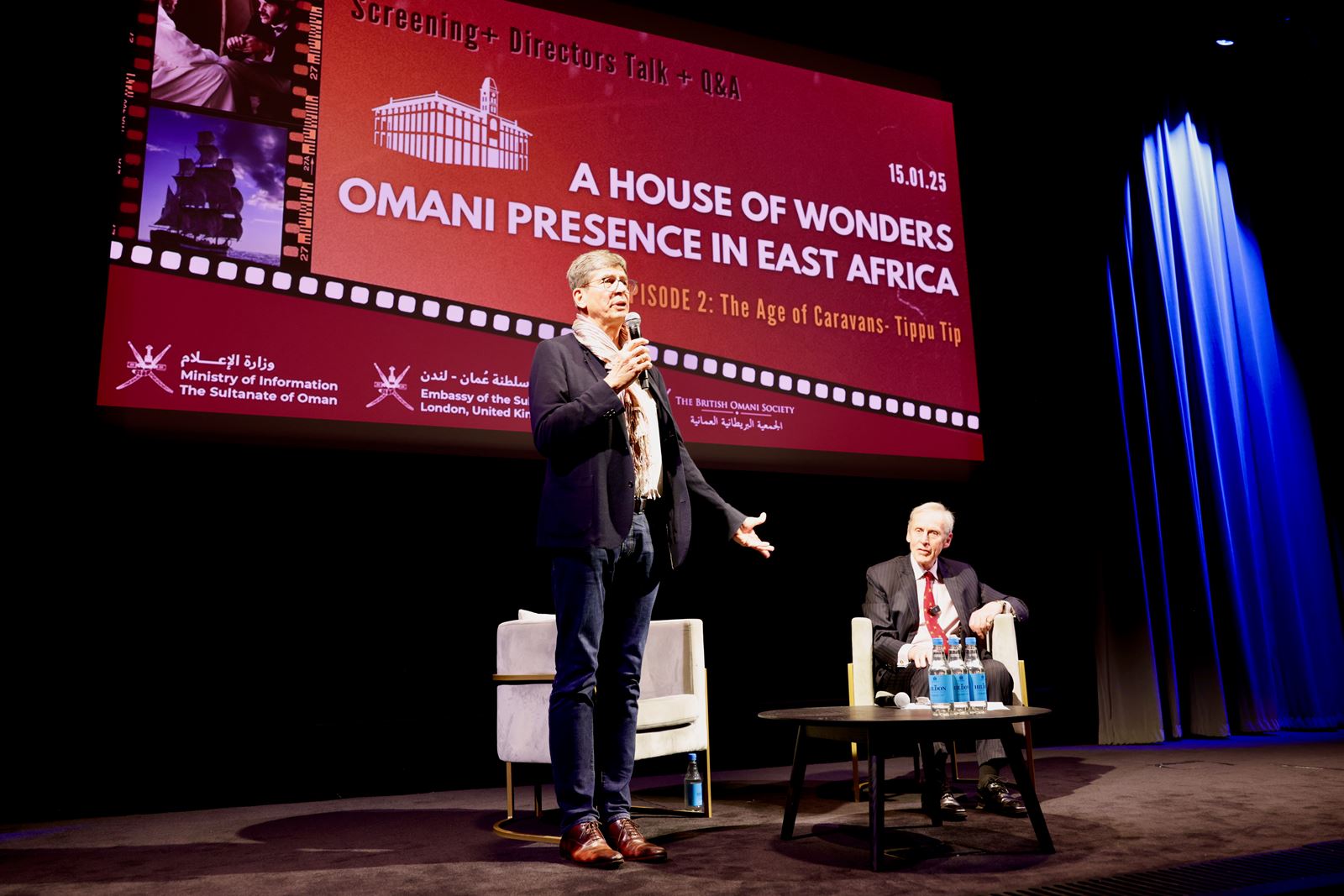

On January 15th 2025, The British Omani Society hosted the London premiere of the 2nd episode of the award winning film A House of Wonders entitled ‘The Age of Caravans -Tippu Tip’ at the BAFTA 195 in Picadilly.

We were honoured to welcome the esteemed Omani Ambassador Badr Mohammed Badr Almantheri and representatives from the Sultanate of Oman Embassy in London. The packed house shared in the excitement of this special event, followed by an insightful Q&A with director Friedrich Klütsch and CEO of DeMAX. The Society is grateful to its former Chairman and Ambassador in Muscat, Stuart Laing, for introducing and chairing the event, and for jointly answering questions with Friedrich Klütsch after the screening of the film. The Society is also grateful to the Omani Embassy and Ministry of Information for generously sponsoring the event, through hiring the prestigious BAFTA Auditorium in Piccadilly.

A House of Wonders is an award-winning multimedia project including a series of three films, an illustrated book, and an educational program. The films are narrated from an Omani perspective and can be considered as the missing element to an essential debate.

The project is a German-Omani coproduction investigating the historical relations between Oman and East Africa while taking the arrival of the European colonial powers into account. Narrated by the Beit al Ajaib as a material witness to this relationship, the films follow the biographies of three pivotal characters covering a span of 150 years. The film won first price for documentary at the ASBU in Tunis in June 2024. The second episode of the film discusses elements of exchange between Oman and East Africa by tracing the life and deeds of one of the most controversial characters in the Sultanate's history.

We had the chance to ask the director Friedrich Klütsch a few questions about the second episode, in which he delved into some of the creative decisions made in the film, Tippu Tip's legacy, and his choices in portraying moments in history:

Q: The film is narrated by the House of Wonders itself, which is an interesting way of telling the story and makes it an important character in the film. What inspired this creative decision?

Friedrich: During production and post production of A House of Wonders, we experienced several magical moments. This was certainly one of them.

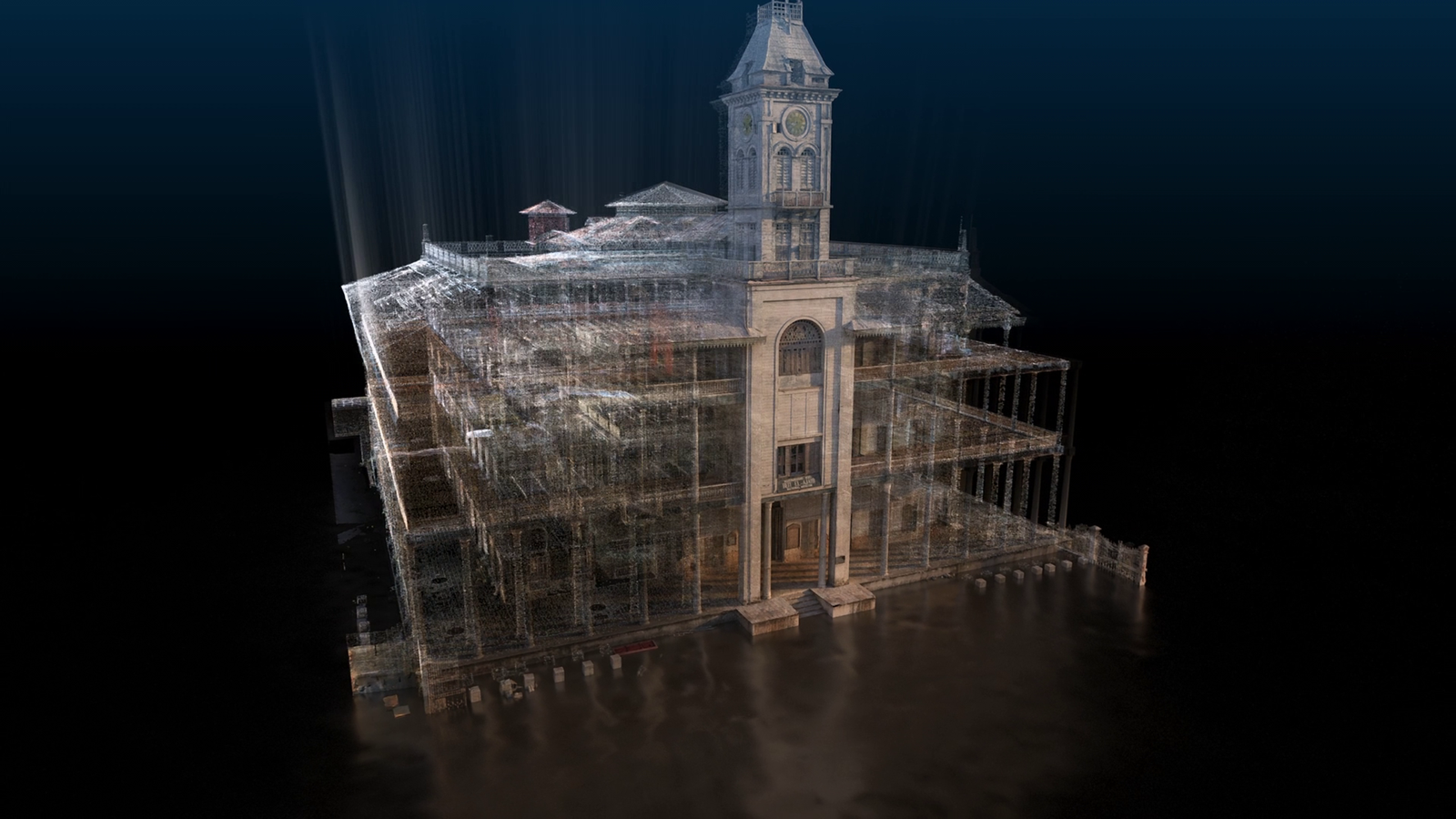

Due to the outbreak of corona epidemic, production was suspended, and we had extra time in the editing suite. My editor Claus Strigel and I were editing a sequence on a team of geomatics from Cape Town University, who were doing a LiDar scan of the House of Wonders building in Stonetown Zanzibar. We had asked them to come to Zanzibar to do scans of the Beit Al Ajiab as well as of Bet il Mtoni, the rural palace of Sayyid Said bin Sultan. In both cases, the Zamani team had done complete scans of the buildings including every room, staircase, etc. at a very high resolution. So while we were grounded in Munich and looking for things to do, we asked Cape Town to render a few images from the scans just to give us an impression of what they would look like. A couple of hours later we got first renderings from the point cloud, which they had acquired on location. We were flabbergasted, to say the least. The visual potential was immediately visible. While we kept experimenting with the data, we developed the idea of using the surfaces inside the House of Wonders as an exhibition space, and the doors and windows as transitional gateways. Over the next few days of editing, the House of Wonders became a pivotal element of the narration. It became the starting, the connecting and the end point for all of the episodes.

We had 40 page scripts for every episode and none of this was written down. It all developed as part of the dialogue between artist and footage. It's an experience that I have made a couple of times in my career. If you have enough time to listen to your footage, it will talk to you. At some point, the house of wonders began to speak to us. It had a female voice. And this is, why in the end the House of Wonders is narrating all of our epsiodes. Kind of wondrous, isn't it?

Q: Tippu Tip is the central character of the second episode. Did you have any specific goals in mind in terms of conveying his story to the world? Are there any specific aspects about him that you felt were important to shed a light on?

Friedrich: Hamed Al Murjebi, who we know as Tippu Tip, is certainly one of the most controversial characters of Omani presence in East Africa. Whenever you start researching on him, Google or ChatGPT will spit out the profile of one of the most notorious slave traders of the 19th century. It will take quite some time to change this, but this should not keep us from starting the job.

Tippu Tip did have many slaves on his plantations on Zanzibar. He will have had slaves in his households in Stonetown and elsewhere. But this does not distinguish him from anyone else of his rank and class at the time. We must acknowledge that a big part of the wealth and the achievements of the Sultanate of Zanzibar had been built on slave labor. But this also applies to London, to Brussels, to Paris, to Berlin, to New York, and to the big African chiefdoms as well. Pointing fingers will not help, when we try to get to terms with the era of slavery.

Tippu Tip, and this is the main argument to choose him as the protagonist for an episode on The Age of Caravans, was not only the most prominent, but also the most important caravan trader of East Africa. Regarding the porters, who he engaged for the caravans that he lead, there can be no doubt that these women and men were self-employed, well paid migrant laborers. This information might be new for some, but it is correct nevertheless.

Q: You touched a bit on the relationship between Tippu Tip and his father in the film. Can you speak more on that relationship? In what ways did they clash and in what ways did they get along?

Friedrich: From what we learn from of the autobiography of Tippu Tip, the relationship with his father was quite typical for any father and son relation and is easy to relate to even from a modern perspective. It is about obedience, trust, and the urge to prove oneself. In retrospect Tippu Tip certainly surpassed his father regarding his significance as a caravan trader and as a political representative of the Sultanate of Zanzibar.

Q: The film focused on the Age of Caravans in East Africa and how they were ahead of their time in terms of them requiring specialists with expert knowledge, as well as having set schedules and wages. Was this out of the ordinary for the time?

Friedrich: Archaeological and ethnological evidence tells us that a commercial exchange between the coast of East Africa and the hinterland had been going on for centuries, if not millennia. What changed in the course of the 19th century were the scope and the frequency of the exchange. Previously, trade had been sporadic and limited. The Age of Caravans brought changes to the African societies that were comprehensive. The age of the foot caravans ends with the introduction of railways at the end of the 19th century. The tracks were laid out exactly on the routes that the caravans had used before. The railroad unfortunately didn't have the participatory effect of the caravans and promoted the monopolization of domestic trade.

Q: The film also mentioned how the Age of Caravans brought ideas along with it. What sort of ideas did they bring about?

Friedrich: The exchange between the coast and the interior brought changes in all aspects of life: belief, ways of administration and social organization, food, fashion, tools and weaponry, music, poetry, you name it - these trade routes opened the window to the world, even to those who didn't move.

Q: The film portrayed an interaction between Tippu Tip and Scottish explorer David Livingstone, in which they discussed writing about their discoveries so that they would be remembered. Did Tippu Tip have interest in recording his adventures? In what ways was he concerned about his legacy?

Friedrich: While we know that they met and spent some time together, the dialogue between David Livingstone and Tippu Tip at their encounter in 1867 as displayed in episode two is fictitious. What we wanted to express is first of all that the age of caravans and the age of discovery overlap to some extent. Secondly, we felt that there is a humorous element in the fact that what the European travelers portrayed as discovery was very familiar to the people that lived and traveled in the same places all their life. Finally, Tippu Tip must have discovered the power of the printed word during his lifetime. When he was approached by the German Heinrich Brode on Zanzibar to record his memories, he did agree. Maybe he also wanted to ensure that the image of him that was handed down was not just left to the goodwill of posterity.

Q: The film touched briefly on Tippu Tip’s legacy in Zanzibar and how was remembered. Can you discuss how he is remembered today and how influence has made an impact in the modern day?

Friedrich: On Zanzibar, Tippu Tip is a victim of tendentious and ideologized interpretation of history. The random voices we were able to record in Kasongo in Eastern Congo, including a catholic bishop and the director of a local women's organization, speak a different language. We believe it is time to reassess his role and his contribution to what can be called Swahili Coastal Culture.

Q: The film discussed the decline of Arab influence in the region due to the rising European power. Can you tell us a little about how Tippu Tip viewed this and how his actions were influenced afterwards?

Friedrich: When we are talking about Omani presence in the interior of East Africa, we must keep in mind that we are talking about a few dozen families in each location only. When the European colonial powers begin their 'Scramble for Africa' in the late 19th century, the settlers and merchants of Omani descent didn't stand a chance. Tippu Tip's approval to the appointment as a governor in the Congo was meant to keep whatever influence the Sultanate of Zanzibar had in the interior as long as possible. It didn't work for long.

We know from his autobiography that Tippu Tip objected to any bellicose engagement against the growing European influence. But his son Sefu didn't listen to Tippu Tip just as he hadn't listened to his father.

Thank you to Friedrich for answering our questions and for hosting a great night at the BAFTA!

Have a look at some of the photos from that evening below: